Category : Feature Stories

Published : September 5, 2013 - 3:16 PM

Grasspea, Lathyrus sativus, is a crop with two sides to its personality. Considered both a saviour and a destroyer; in times of famine grasspea is often the only alternative to starvation. Being the hardy plant that it is, it can withstand extreme environments, from drought to flooding, and when all other crops fail grasspea will often be the last one left standing. It is easy to cultivate, and is tasty and high in nutritious protein, which makes grasspea a popular crop in south Asia and the eastern Horn of Africa where it is also grown to feed livestock. Being a member of the legume family, Lathyrus is able to fix nitrogen from the air which means that growing it keeps the soil healthy and well fertilised.

Now, before we make a saint out of the humble grasspea, let us consider some of its more sinister attributes. Eaten in small quantities, grasspea is harmless. However, eating it as a major part of the diet over a three month period can cause permanent paralysis below the knees in adults and brain damage in children, a disorder known as lathyrism. The culprit is a potent neurotoxin called ODAP. This is responsible for the drought and waterlogging tolerance of grasspea but, if taken in large quantities, it brings on the neurological disorder. For example, Ethiopia has seen several lathyrism epidemics in the past 50 years, when hunger overrules the dangers inherent in grasspea consumption. What makes matters worse is that the level of the neurotoxin increases in the crop under conditions of severe water stress which exacerbates the risk of lathyrism at a time when the poorest of the poor have no choice but to rely on the crop for their survival.

According to The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) at least 100,000 people in developing countries are believed to suffer from paralysis caused by the neurotoxin. There are a number of ways of preparing grasspea so that it is less harmful, for example, by washing and soaking the grasspeas and then discarding the water before cooking or by eating grasspea mixed in with other crops. Both strategies are effective in reducing the risk of lathyrism however in a famine where water and other food sources are scarce, detoxification of grasspea may be harder to implement.

Thanks to the Grasspea

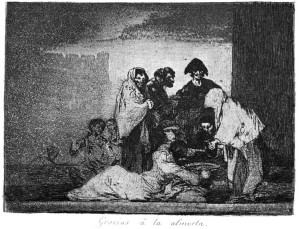

The adverse neurological effects of eating grasspea have been known since prehistoric times. Ancient Indian texts described the disorder and even Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine himself, mentions a neurological disorder caused by eating a Lathyrus seed in 46 B.C. in Greece. Grasspea was served as a famine food during the Spanish War of Independence against Napoleon and below is one of Francisco de Goyas famous aquatints, Gracias a la Almorta (Thanks to the Grasspea). It captures the hardships of the time through its depiction of the poor surviving on grasspea porridge, one of them lying on the floor, already crippled by it.

For all the effort involved in cultivating grasspea and making it safe for consumption you might think it easier to abandon the crop altogether. However, things are not as straightforward as all that. Grasspea continues to be the ultimate safety net for subsistence farmers in the poorest parts of the world and provided that consumption does not reach that critical level it is safe and nutritious to eat. Quite simply, grasspea is too important to do away with altogether.

Breeding low toxin varieties

Crop diversity is the key to overcoming this paradox and is the only thing that can put an end to the good cop/bad cop antics of grasspea. The International Centre for Agricultural Research for Dry Areas (ICARDA) is working with Ethiopian breeders to develop cultivars of grasspea with low levels of the neurotoxin ODAP. Toxins found in African and Asian grasspea plants are seven times more toxic than the Middle Eastern varieties. The new ICARDA hybrids have levels of the toxin high enough to keep up the crops resilience to drought and flooding, without being damaging to human health. The Centre for Legumes in Mediterranean Agriculture (CLIMA) is also conducting important research in this area and has recently produced a low toxin variety. Hope is on the horizon but much more work needs to be done to produce locally adapted, low toxin varieties and to distribute these to farmers.

Crop Wild Relatives: A source of genetic diversity

The wild relatives of grasspea are an important source of genetic diversity for the cultivation of low toxin varieties. Grasspea is one of the 29 priority crops that are the focus of the Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change project executed by Kews Millennium Seed Bank and the Global Crop Diversity Trust. By collecting the wild relatives of crops such as grasspea and making their seeds available to breeders, useful traits such as lower toxicity levels, in the case of grasspea, and resistance to pests, diseases and environmental stresses can be passed on to crops, making them more resilient and better equipped to deal with climate change. The development of low toxin varieties of grasspea is a matter of food security and is something that will have a direct impact on the health and livelihood of thousands of people. Grasspea takes on a special importance in the light of climate change since tolerance to drought and flooding are characteristics that give the crop an advantage in stressful conditions.

Who knows, maybe grasspea will be up for sainthood after all!