Category : News

Published : September 25, 2017 - 2:43 PM

Written by Oriole Wagstaff, CWR Technical Officer

On a cold and rainy morning in April 2016, Georgian botanist David Kikodze stood with his back to the Black Sea and listened to waves crashing behind him. He gazed out and watched his colleagues, Manana Khutsishvili and Izolda Machutadze, pacing around, eyes glued to the beach while studying the plant-speckled sand around their feet. They were searching for the elusive sea medick, Medicago marina L., a wild relative of alfalfa. As he shivered in the rain, David wondered if they would ever find it.

Alfalfa’s crop wild relative

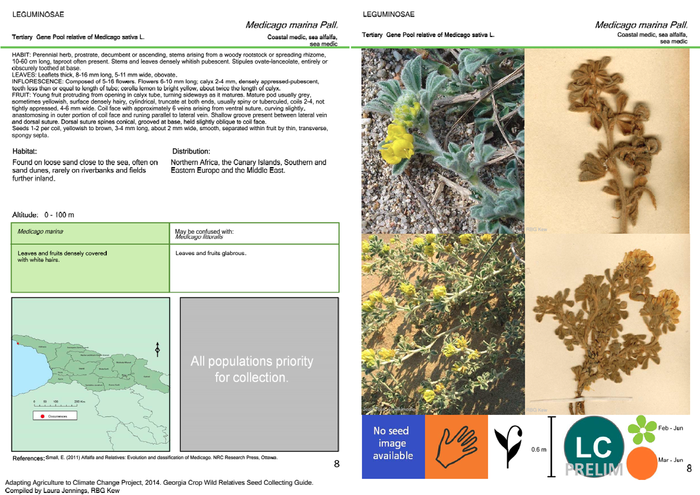

More than 80 countries rely on alfalfa for animal feed. Its nitrogen-fixing ability makes it a very efficient crop, producing high-protein feed regardless of available nitrogen in the soil. As climate change threatens alfalfa production, the need to breed improved, drought-tolerant varieties will become more important.

The coastal crop wild relative, commonly known as sea medick, is thought to contain both drought and soil salinity tolerance. These are traits that domesticated alfalfa varieties will surely need in the coming years.

A gap analysis conducted by the Crops Wild Relatives project showed that there were no ex situ accessions of sea medick in any of the global collections. Medicago marina seeds had never before been collected and conserved in Georgia. David and his colleagues could find very little information on this alfalfa species. His team searched the Georgian National Herbarium but got no leads. They put their faith in whatever literature they could find and in their Crop Wild Relatives Collecting Guide. David and his colleagues were confident this plant would be in Georgia, somewhere.

Colleagues from Batumi Botanical Gardens had tried to locate the seaside plant in 2014 but were unsuccessful. It had last been spotted on the coastal areas of the Black Sea more than 15 years ago.

Destination Kobuleti

The search began in Kobuleti, a Black Sea resort near the Turkish border and 500 kilometres from Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital. This was a new site to be explored by David and his team was confident of an early success. But an early success proved elusive.

“We were perhaps overly optimistic, I guess,” David said. He had instructed his team to pack for only one night. “We searched day and night, night and day, for three days with no luck.”

The Georgian botanist – our protagonist

Georgia’s Institute of Botany is one of 25 partner organizations in the collecting phase of the 10-year Crop Wild Relatives Project, led by the Crop Trust and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew’s, Millennium Seed Bank. Georgia signed up in 2014 and was one of the first partners to join this global effort and the third to successfully complete their collecting goals.

The Institute’s deputy director, David Kikodze, led Georgia’s collecting effort. Having studied biology in Georgia, David joined the Institute of Botany in 1992 after completing post-graduate courses at Komarov Botanical Institute in Russia’s St. Petersburg (then Leningrad). For the past 25 years, David has been collecting and conserving seeds. David’s interest in crop wild relatives has grown from initial curiosity to understanding the sustainability of their populations and exploring the peculiarities of their geographical distribution.

Three days of searching

For three days the team went back to the coast, searching, desperately for this yellow mystery.

“Honestly, we were not really very well prepared for the trip. Our original plan was to arrive on the site, collect, pack up and return the very next day,” David confessed. “We did not even have food.” But for David food isn’t too much of a problem. “When I’m looking for plants I forget about everything. I can go without food and drink.”

But he is the exception. “Usually on collecting expeditions we take a lot of food. We’re Georgians – we eat and drink a lot,” he adds. Luckily for the team, Kobuleti is a tourist destination with no shortage of places to stock up on food.

David’s team searched for up to 10 hours day after day, covering more than four kilometers every day. After a somewhat chaotic study of the survey area the first day, and failing to find the target species, they decided to use a more systematic approach and split the study area into quadrats. Each team member was then responsible for finding the plant in their own quadrats.

In the evening, they searched for clues in the literature at the Batumi Botanical Garden’s herbarium. “We even looked through old Russian books and unpublished hand-written field notes from Soviet Union times that are archived there,” David explains. Each night they left the library with no clues or hints. They walked back tired, sweaty, feet hurting to their tents on the garden’s grounds.

“When you are working hard, day and night, around the clock, and you come back empty-handed, it’s very disappointing,” David said. Maintaining their motivation was challenging. David recalls thinking back to a humorous comment an old friend had once made: life is hard but fortunately it is very short. Still, they did not give up. With a good team to support each other and a good supply of Saperavi, Georgia’s flagship red wine, in the evenings, the team’s determination stayed strong.

What drives seed collectors?

For David, being a seed hunter means being part of a global team and knowing the impact this project may have globally.

“What we do, we do for people, for everyone in the world. We may find plants that lead to new genetic knowledge that can improve future crops,” David said. “Humankind depends on these crops. This makes us feel very special, that we contribute to increasing our knowledge of these wild plants, for conserving and breeding them in the future. It’s a very special feeling to know that you collect here, and, at the same time, other people are collecting in other parts of the world. Conserving diversity for the future of humanity makes my work really important.”

“You never really think about these things in the field when it’s cold, or when you are hot and wet,” David laughed. “But that’s what drives us to get out there.”

The crazy botanist

Botanik (ботаник) in Russian translates into botanist, but is also slang for crazy person. “There is a grain of truth in this,” David laughed. “When we search for these plants, hours after hours, and there are thousands of people enjoying themselves on the beach, we do think we are a bit insane.”

Kobuleti is quickly becoming one of Georgia’s major tourist destinations. Increasing numbers of tourists have led to rapid and extensive development of almost all available lands within Kobuleti. Russian tourists are flocking to the area, appreciative that many locals are fluent in Russian, but Ukrainian and domestic tourists have also been attracted to the area. “One year you may come here and see nice beaches and countryside,” David said. “The next year there are many buildings and hotels instead.”

By the end of day three, David and his team were becoming more convinced that this rapid development might have wiped out this sea medick population. “The seaside is an arena of rapid development. Some 100 years ago, there could have been a wild beach, but now it’s like Las Vegas. That’s why it’s so important to find these untouched patches of wild nature – to collect the genetic diversity before they disappear.”

A collector’s frustrations

Collecting can be very challenging. It is a balance between timing and opportunity. David’s team conducted nearly 100 trips over three years, but not all of these trips were successful. On average, one out of five times they came back empty handed.

“Some plants grow in the east, some in the west of Georgia. Some grow in the mountains, and some in the lowlands. So we try to split the collecting target between the team, and I think this helped us collect almost all that we committed to. It was a combination of teamwork and individual trips,” David said.

Even if you find the plant you are looking for you may be out of luck. “If you miss the time when seeds are mature, by a matter of weeks or even days, you may have to wait for a whole year,” explains David. So there is pressure to get to the locations ‘on time’. But David does not let this pressure get to him. Instead he will visit a site multiple times – first to confirm the location of populations and collect herbarium specimens, and then he will return when they are in seed. This is the nature of collecting.

The dividends of persistence

After the third day, the team’s frustration began to grow. The Kobuleti region of Georgia is known as a “rain pole”, and the constant rain made the expedition more difficult. But the seed collectors were determined. Even when the rain kept the locals and tourists at home, David and his team of botanists worked through the constant downpours.

Deciding to split the territory into three areas, the team searched separately. On the fourth day, they were rewarded for their persistence. Local botanist, Izolda Machutadze, stopped in her tracks and gazed down at the simple plant which had proved so elusive. A patch of Medicago marina covering no more than 100 square meters lay before her. She looked up, smiled, calmly revealing to Manana and David that she had found it.

“Manana and I were the happiest people in the world at that moment – my first thought was that life is so beautiful sometimes!” David said.

Partnerships at work

In Georgia, as in other countries that are collecting crop wild relatives, teaming up with local experts has proven vital to the success of their collecting expeditions.

“Isolda was indeed instrumental,” David said. “I love working with really experienced botanists, they are knowledgeable and enthusiastic; it is enjoyable to work together.”

This creeping plant, no more than 20 cm in height with small bright yellow flowers, spiky seed pods, and a coating of fine white hairs, had both tested and rewarded David and his team.

“The worst thing is when you go in search of something and you don’t find it. But when you eventually do find it, it’s amazing. I wish everyone could experience that feeling of searching and finding plants.”

Turning a challenge into a success: “I wasn’t sure whether or not we would be successful; it hadn’t been seen recently.”

Safeguarding our crop diversity

David’s experience with finding sea medick echoes a warning about the current threats facing the known and undiscovered plants that may one day prove essential. “Rapid development means this population may be lost within 10 years,” David said. “And it’s very likely that we will be the last people to ever collect and conserve this specific population.”

David’s team notified the Georgian Minister for Environment about their concern for the increasing development threats to the only remaining population of sea medick in the area. “Though seeds will now be conserved in genebanks, it’s important they are also conserved in their natural habitat,” David said.

The team plans to visit the site again. “Firstly, because I want to make sure this small population is still there and to further think about to how protect it,” David said. “And secondly, because it will always remind me of the day when we first found it.”

The Institute of Botany finished their collecting in 2016. In three years, the Institute of Botany collected 15 species of crop wild relatives. They achieved a total of 110 seed collections, which is 10 more than they had agreed to collect. Thanks to their hard effort, crops including alfalfa, carrot, faba bean, grasspea, vetch and wheat will potentially benefit from the hidden traits in these crop wild relatives.

This effort has not only expanded the international collection of crop wild relatives that are now available for researchers across the world, but it has also strengthened the Georgian national collection which is safeguarded at the National Botanical Garden of Georgia.

The knowledge and experience gained from working on this project has provided David’s team with the tools and partnerships to support future projects.

“It was an excellent experience to be a part of the CWR project team,” David said. “I learned a lot collecting CWRs in different habitats and geographic locations, which I had less experience with in the past. It was exceptional to study the diversity of each target species,” David said.

Lessons learned

Having finished their CWR collecting, David and his team are continuing to challenge themselves, working with the Millennium Seed Bank and other partners, on a number of projects to conserve many more Georgian species.

David can summarize his advice for future collectors with four points:

- Knowledge: knowing the characteristics of the target species, where it has been found and when it will flower.

- Patience: it takes time to find the target species and collect them at the right time.

- Intuition: comes with experience. “Once you have studied all the literature, you have to guess where to go and what to expect,” David said. And lastly,

- Optimism: “Never give up. Keep searching and you will find what you are looking for – sooner or later.” But preferably, sooner.

Collecting of sea medick specimens by David Kikodze and Manana Khutsishvili from Georgia’s Institute of Botany , assisted by Izolda Machutadze from Batumi State University.

***

This project is part of ‘Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change: Collecting, Protecting and Preparing Crop Wild Relatives’, funded by the Norwegian Government and coordinated by the Crop Trust and the Millennium Seed Bank, Kew.

All material collected within this project is available under the terms of the Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA) within the framework of the multi-lateral system, as established under the International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA).