Category : News

Published : May 4, 2017 - 7:20 PM

Written by Elsa Matthus, CWR Project Correspondent

As part of the project “Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change: Collecting, Protecting and Preparing Crop Wild Relatives”, a global network of lentil scientists and breeders are working to cross and evaluate wild and cultivated lentil species. The cultivated lentil is a world favorite, but the crop has become too narrow (genetically speaking).

A Tiny Superstar

Lentils grow well on poor soils, come in a variety of colors and tastes, and are packed with protein and nutrients. Whilst major crops like rice, wheat and maize gulp down fertilizer as if there literally was no tomorrow, the modest lentil fixes its own nitrogen from air and thus requires little inputs.

Beyond the field, lentils are the main – because affordable – source of protein in many diets low in meat, and a staple food in countries such as Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. Along with its relatively tiny ecological footprint, the lentil is also hailed as a ‘superfood’ by hipsters and millennials: think bowls of steaming orange lentil dal, with added Instagram filter. To top it off, lentils cook fast – some varieties even faster than rice – and do not need to be pre-soaked. Hashtag ease of preparation, hashtag energy saving (which is quite a deal sealer if you have to gather wood to cook your meals).

The World Loves Lentils

Global lentil production increased almost fivefold since the 1970’s. Many countries like their equivalent of Spain’s ‘lentejas con chorizo’, but have to rely on imports, as national production cannot satisfy the demand. On the other hand, there is Canada, a country that hardly grew any lentils before the 1970’s but is now, by far, the biggest exporter in the world, shipping lentils of all colors to 110 countries.

“In the last 40 years, the world’s population has gone up by 80 percent. That’s why we are all worried about food security, but at the same time, lentil consumption has gone up 350 percent,” says Professor Albert ‘Bert’ Vandenberg from the University of Saskatchewan, in the middle of the Canadian prairies. Vandenberg is one of the reasons Canada is such a successful lentil producer nowadays. He has been called the ‘godfather of lentil breeding’, and leads the world’s most successful lentil genetic improvement program. He is also just a pretty cool guy, wears a leather jacket and speaks with the ease of somebody who knows his work matters. He knows the world loves lentils.

Narrow Escape

But here comes the bad news. The genetic diversity of our cultivated lentils is too narrow. This narrow genetic background leaves the little lentil defenceless when facing many of today’s stresses, such as drought and fungal attack.

A lentil plant which has lost the battle. First signs of the fungal disease Stemphylium blight are the leaf and floral tissue to go brown and fall off. See all the little water droplets? That means perfect humid conditions for the fungus to thrive on this field site in Bangladesh.

Photo: Ph.D. student Rajib Podder

How did this happen? Lentil domestication took place about 10 000 years ago in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent, nowadays Turkey and Syria. The cultivated lentil has come a long way since then, with only the best tasting and highest yielding lentils being selected and grown again and again. During this domestication, other useful traits such as stress resistance have been largely neglected. That is how the process goes for many crops. Unfortunately, the genetic bottleneck is particularly extreme in lentil, as the lentils we are cultivating have very much the same build, genetically speaking. The variation in their genetic toolkit, still there in the wild lentils, is gone in the cultivated ones. Lentil breeders around the globe agree on this lack of genetic diversity, and facepalm in unison.

Singing and Screaming

Fortunately, the wild, and genetically more diverse, lentils are still out there, in the mountain ranges of Southwest Asia to North Africa. No human has touched them for the past few thousand years, give or take a few out on a stroll. These wild relatives look less groomed than our cultivated lentil, but are still closely enough related to be compatible for crossing. Cultivated lentil, Lens culinaris Medik., has six so-called ‘crop wild relatives’.

A wild lentil field in Cordoba, Spain. The lentil plants are grown for seed multiplication, so the researchers on this Crop Wild Relative project will have enough seeds for all their field trials.

Photo: Albert Vandenberg

“These crop wild relatives are a million years old, so they have been through many cycles of climate change and accumulated many useful genes along the way. They are a bit like a gold mine”, says Vandenberg.

Depending on how closely related the wild lentils are to the cultivated ones, they are classified into anything between the primary genepool (think: cousins) up to the quaternary genepool (think: cousins a few times removed, but hey, they never showed up to family gatherings anyway). The process of crossing these wild species with cultivated lines is a big part of ‘pre-breeding’, a step-by-step process to gradually introduce diversity back into cultivated varieties.

It isn’t always easy. Vandenberg explains that there are two kinds of breeding in lentil. “In the primary genepool we call it ‘Singing,’ Systematic Introduction of New Germplasm. But when it comes to the secondary and tertiary gene pools, we call it ‘Screaming,’ which is Systematic Creation of Exotic and really Awful Material.” He laughs. “Or: Slow Critical Research that Eats All your Money.” The quaternary genepool looks like it does not want to cross in at all. At times in pre-breeding, it’s easy to wonder if it’s really worth it.

Lentils Under Attack

Somebody needs to come to the cultivated lentil’s rescue, that’s for sure. Look at most lentil fields around the world and you will find struggling lentil plants. Take Turkey, for example. Turkish lentil production has been declining for the last decade, even though, as Professor Behiye Tuba Bicer from Dicle University in Diyarbakır, Turkey, adds, “lentil soup is loved by everyone”. Thousands of years ago, this area in Turkey was the birthplace of lentil. The lentil crop has been growing in these semi-arid and arid landscapes just fine, and thus traditionally without irrigation. Due to changing climate and increasingly extreme weather, however, drought periods have become too severe for even lentils to stomach. Farmers have moved into irrigated crops such as cotton, which are less prone to fail due to unreliable weather.

Lentil evaluation in action. The ‘godfather of lentil breeding’, Dr. Bert Vandenberg (left), and Dr. Beybin Bucak inspect the growth of different wild lentils on a field in Turkey.

Photo: Kirstin Bett

Extreme weather has not only brought drought, but also heavy rains. If a year is too wet, fungi spoil the lentil crop. One fungus in particular causes Stemphylium blight, a disease that has been on the rise in recent years and devastated lentil crops in the Indo-Gangetic plain. More recently it has also been reported in Canada. The disease cannot be controlled by just eliminating the crop for one season, as it survives on other plants. The only way of making lentils resistant to Stemphylium blight is through breeding varieties resistant to the fungus.

As if this was not enough, another threat is hiding below ground: Orobanche, or broom rape, a parasitic plant that literally sucks the life out of other plants. Orobanche infested lentil fields are difficult to cultivate without yield losses. “Producers have been giving up lentils due to Orobanche,” explains Bicer. “Now they ask for new varieties which are resistant to Orobanche.” As with Stemphylium blight, resistant varieties are the most sustainable way to outwit Orobanche.

Who will survive? This mystic field site in Bangladesh offers the perfect humid conditions for a lentil-harming fungus to grow. Wild lentil crosses are evaluated for their tolerance to the fungus, causing Stemphylium blight.

Photo: Albert Vandenberg

Beautiful little suckers. The light pink flowers belong to Orobanche, a parasitic plant that attaches to lentil roots and sucks nutrients and water, here on a field site in Spain. Some of the wild lentils screened in this Crop Wild Relative project have shown resistance to Orobanche, giving the parasite no chance to rob them.

Photo: Albert Vandenberg

Full Steam Ahead in the Greenhouses

Vandenberg and other researchers are banking on wild lentils. Crossing wild and cultivated lentils, however, is no easy task. Dr. Richard Fratini, working in the group of Professor Marcelino de la Vega at the University of León in Spain, is an expert in making the little lentils cross. He has already successfully crossed a couple of wild lentils with cultivated lentil, with work still ongoing as part of the Crop Wild Relatives project.

These days, he is anxious. He has just transferred eleven little lentil plants to the greenhouse and planted them in the soil, after pampering them for weeks in optimal laboratory conditions. The plants are the result of crossing cultivated lentil with one of its wild cousins, Lens lamottei.

Lens lamottei is in the secondary genepool, hence it does not cross easily with the cultivated lentil. To appreciate those eleven little plants, one has to know their story: Fratini has been working on close to 1,000 crosses between cultivated and wild lentil. Yes, that was one thousand. “I did these crosses in three weeks, and basically lived in the greenhouse”, shared Fratini. Last year, he spent Christmas day doing crosses.

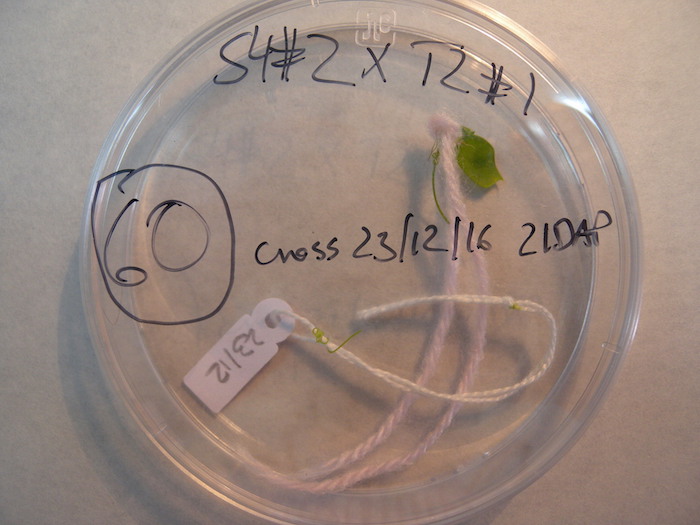

The Christmas cross. Dr. Richard Fratini crossed wild and cultivated lentil, in the greenhouses of the University of León, Spain. Three weeks later, a green pod with a fertilized ovule inside has formed, from which Fratini will need to ‘rescue the embryo’, a common but tedious procedure in lentil breeding.

Photo: Richard Fratini

When the lentil plants flower, Fratini needs to choose which lentils to cross, pollinating the chosen ones by hand. Very steady hands, sharp-pointed forceps and the eyes of a hawk (or a good optometrist) are essential. Do this with a thousand flowers. From these, Fratini was able to extract 79 properly fertilized ovules. And that’s where the tricky bit starts. From these ovules (tiny) one needs to pick out the embryo (even tinier).

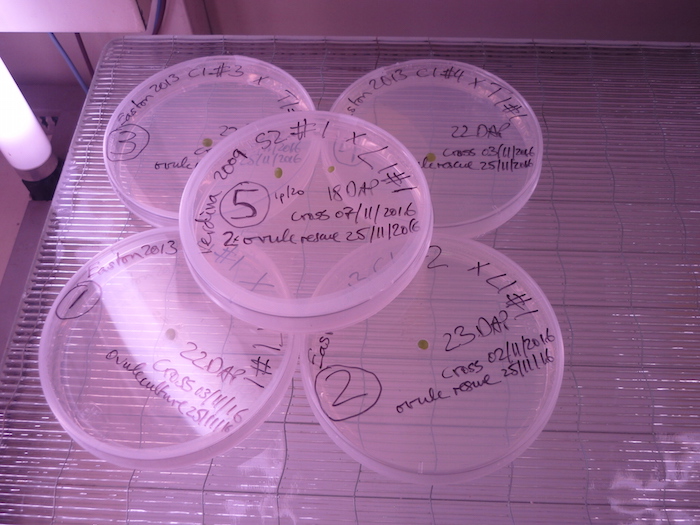

Tiny lentil ovules in petri dishes. The fertilized ovules are extracted from the lentil pods, and grown with supplying optimal nutrients, light and temperature. The ‘embryo rescue’ process is necessary when crossing wild and cultivated lentils, as the crosses are often too weak to survive and need to be pampered.

Photo: Richard Fratini

Fratini was left with eleven embryos that were strong enough to develop a proper root and shoot system. It is these eleven plantlets that he transferred to the greenhouse on a Friday. He checked on them on Saturday, and he checked again on Sunday. On Monday, all eleven were still alive. Once big enough, he will need to confirm if they are real crosses and make fertile plants that set seeds. If no seeds are set, they are of no use and it is back to square one.

“It is a long slog to get interspecific lentil hybrids, and it can feel like torture” says Fratini. And then he waves his hand as if all of this was nothing. “Ask Bert [Vandenberg]; his lab did thousands and thousands of crosses to get one single successful hybrid” with another wild species from the tertiary genepool. The words of ‘tertiary genepool’ send chills down the spine of the hardiest breeder.

Who is your daddy? A four month old lentil plant, which is used in the crossing program at the University of León, Spain. Little white labels are dangling from every flower that has been pollinated using pollen from another lentil plant. The labels carry all the information about who the daddy is, and when the cross was done.

Photo: Richard Fratini

Lentil teenager close-up. This tiny lentil plant grew out of an embryo culture, and is the result of crossing a cultivated lentil with a wild lentil, Lens lamottei. The tiny lentil plant is magnified with binoculars, to check its growth. In reality, it is the size of a pinhead.

Photo: Richard Fratini

Superpowers at Bay

The successfully crossed lentils lines have a shuffled genome, with genetic bits and pieces from both wild and cultivated lentil, and are the tools that unveil the superpowers hidden in wild species. To do that though, these half-tame-half-wild lentils need to be evaluated in the field, taking the research a crucial step further towards breeding stress tolerant lentil varieties.

Vandenberg sighs, as he reflects on his experience of these trials. His team multiplied the seeds of the lentil crosses in Canada. Weather was good that year. Seeds were tightly wrapped in little bags, and sent off to the collaborating partners in Turkey, Morocco, Spain, Nepal, Bangladesh and Ethiopia for field trials the following year.

Moroccan lentil fields. After crossing wild and cultivated lentils, the offspring is evaluated in the field. As each line has a different mix of wild and cultivated lentil genes, they respond differently to the environment. The hunt is on: Which half-wild-half-tame lentil has the optimal mix?

Photo courtesy: Benjamin Kilian

Waiting for the parasite to strike. Researchers Dr. Beybin Bucak, Dr. Kirstin Bett and Dr. Tuba Bicer (left to right) inspect a lentil field site in Kiziltepe, Turkey, for signs of infestation with the parasitic plant Orobanche.

Photo courtesy: Albert Vandenberg

Light at the End of the Lentil Field

No matter. Lentil researchers cannot be knocked off course. Rather, Vandenberg gets excited: “If you are lucky and you work hard, you can actually harness genetic diversity, and whip it into shape. The most interesting part of the experience was that initially we only wanted to solve a problem for one disease. But over time, as we developed this set of interspecific recombinant lines, they were very terrible looking plants, but we – almost serendipitously – started observing them in the field and realized that we were up to five different disease resistances from the same original crosses. That’s phenomenal!”

After the setbacks of the first field trials, subsequent years have been more generous in providing weather and political conditions conducive to the project. For example, field experiments in Turkey have shown that one of the wild lentils is resistant to Orobanche, whilst the cultivated lentils suffer from the parasite. The same was observed on an Orobanche infested site in Ethiopia. “This project is seen as a hope for farmers,” shares Bicer. Vandenberg adds contentedly: “We have extended our genetic diversity, and we even see an increase in yield.”

The relationships built between the collaborators during the tough times are a big step forward. “Having a good network is very important”, Vandenberg stresses. “You build the relationship first and then research will move along”.

When asked what his ideal lentil would look like, he leans back, thinks for a moment, and says: “You know, it wouldn’t be one. There would be many.”

***

The work on lentil and other crops under the Crop Wild Relative project is funded by the Norwegian Government and coordinated by the Crop Trust and the Millennium Seed Bank, Kew.