Category : News

Published : November 12, 2014 - 1:13 PM

Danielle Haddad investigates the importance of cowpea as a food crop in the diets of many in West and Central Africa, and how the cultivation and consumption of this crop could secure food for thousands of people.

The Worlds Food:

Fighting to feed the hungry mouths of today is already a challenge, but in order to feed a population approaching 9 billion people by 2050, we will need to increase food production by 70%. This will be all the more difficult if we continue as we are, generating 80% of the global populations calorie intake from just 12 plant species. To move beyond our risky reliance on such a small number of plants, we need to look again at resilient crops the world has tended to ignore like cowpea.

Tuck into Cowpea:

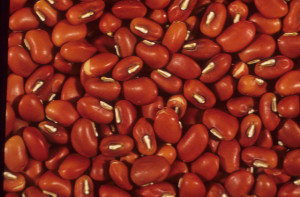

Following on from this years training course in Uganda, we delve deeper into the use of Cowpea in diets and food security in West Africa. Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) is a remarkable species known in many parts of the world by different names like black-eyed bean, black-eyed pea, China pea or marble pea. It was first domesticated in West Africa 5000-6000 years ago, and today is grown commercially in over 33 countries. It is a tough crop which thrives in sandy soils, and is one of the most important and dependable legumes grown in West and Central Africa because of its incredible tolerance to drought. It provides good ground cover, suppresses weeds and fixes nitrogen from the air, making its own fertilizer for the soil. Therefore, growing cowpea can contribute significantly towards farm fertility in marginal lands.

High levels of protein (24%) and carbohydrates (64%) also make cowpea an excellent contributor towards minimising malnutrition and hunger. Cultivated for food, fuel and fodder as well as a multitude of medicinal uses, it has significant importance in the livelihoods of the rural poor in West and Central Africa. Cowpea is so versatile in the ways it is utilised as a food crop that there are vast arrays of cooking methods found world-wide. It is mainly grown for its seeds, which can be made into a nutritious and delicious soup or even an alternative to coffee. In West Africa the seeds are also ground into flour and combined with onions and spices to form cakes, which may become deep fried akara balls or steamed moin moin. The flour is also used to produce crackers and baby foods which are consumed in Senegal, Ghana and Benin. However, it is not only the seeds that are used for food; the leaves are also prepared as a vegetable by steaming or boiling, and provide a tasty and fresh side dish. Towards the end of the dry season, when food is scarce and diets are lean, the leaves are at their best. They can also be preserved through sun-drying and eaten dried. Roasted and stewed cowpeas are also regional favourites in the United States, while in Asia cowpea pods are cooked and consumed whole. The roots are occasionally eaten in the African regions of Ethiopia and Sudan.

In many places cowpea is just as important to livestock diets. The plant is grazed by livestock or mixed in with dry processed cereals for animal feed throughout West Africa, Asia and Australia. In Nigeria some varieties are cultivated for their strong fibre, which is used to make fishing gear as well as good quality paper. Medicinally cowpea provides a variety of treatments from the whole plant. For example, the leaves and seeds can applied to skin infections as a poultice; the leaves can be chewed to relieve toothache; powdered, carbonized seeds can be applied to insect stings; and the roots are used to treat epilepsy, chest pain, constipation and even snake bites.

Cowpea Wild Relatives

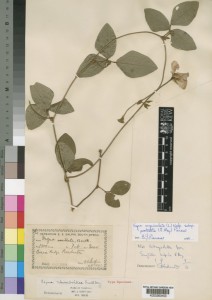

There are eleven primary wild relatives of cowpea that are native to East, Central and Southern African countries. The subspeciesletouzeyi is native to countries such as Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, while another subspecies baoulensis is also native to Cameroon and countries across West Africa. These particular cowpea wild relatives have their herbarium vouchers stored at Kews Herbarium as well as a range of other institutions. The herbarium vouchers are stored for numerous reasons, including research and historical records. The project also uses herbarium specimens for Collecting Guides issued to partners to facilitate their seed collecting trips. The Guides and herbarium vouchers enables researchers and collectors to clearly identify and locate the crop wild relatives of cowpea. The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) have been working with partners across developing countries and research institutes since 1970 on cowpea as a mandate crop, including efforts to utilize the wild relatives for cowpea improvement. They are involved in developing and distributing cowpea seeds of new germplasm lines to over 60 countries. Their work has seen them build up a collection of 15,000 accessions of cultivated cowpea and 1,500 accessions of cowpea wild relatives.

The remarkable cowpeas full range of uses makes clear the importance of cultivating diverse crops to give farmers more options for adapting to climate change. There has never been a more pressing time for the collection, protection and preparation of the wild relatives of crops like cowpea to tackle an ever-changing climate. With its unique ability to provide nutritionally valuable food for people and livestock, it is vital that we protect this important crop and its relatives for future use.

Story written by: Danielle Haddad

Contributors: Gwilym Lewis and Sarah Cody

Documents

- Beentje, H. (2010). The Kew Plant Glossary: an Illustrated Dictionary of Plant Terms. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

- Brink, M. & Belay, G. (2006). Cereals and Pulses: Volume 1 of Plant Resources of Tropical Africa. PROTA.

- Duke, J.A. (1981). Handbook of Legumes of World Economic Importance. New York: Plenum Press.

- Mabberley, D.J. (2008). Mabberleys Plant-book: a Portable Dictionary of Plants, their Classification and Uses. Third edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (2008). Seed Information Database (SID). Version 7.1. Published on the internet at http://data.kew.org/sid/SidServlet?ID=12273&Num=W98 (accessed 28 August 2013).

- Although every effort has been taken to ensure that the information contained in these pages is reliable and complete, notes on hazards, edibility and suchlike included here are recorded information and do not constitute recommendations. No responsibility will be taken for readers own actions. Full website terms and conditions.