Category : News

Published : May 16, 2014 - 1:46 PM

Keeping seeds for generations to come

The potential of crop wild relatives to improve the crops we eat has been realised time and time again, throughout history. All crops, without exception, have wild origins and their ancestors were, for the most part, weedy, scrawny little things. We can thank selective breeding for transforming them from their humble beginnings into the scrumptious, plump and nutritious vegetables and grains we find on our plates today.

Crop wild relatives are a powerful tool we have to adapt agriculture to climate change and worryingly, many of them are currently threatened and in need of conservation. Crop wild relatives can be credited for traits that make our crops resistant to diseases such as grassy stunt virus in rice and black sigatoka in banana. Crop wild relatives have also been used to increase the yield of wheat and breed drought and salinity tolerance in barley. (See examples here and here).

Crops such as potato, rice, lentil and banana are major food sources for millions of people all over the world and by increasing their genetic diversity and resilience, through the use of crop wild relatives, more people will have access to the food they need. That is why the Global Crop Diversity Trust and Kews Millennium Seed Bank are collecting the seeds of crop wild relatives. This 10-year project is aptly called Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change.

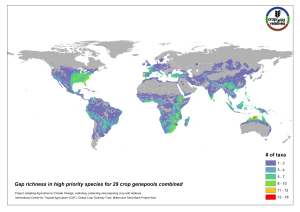

Using the results of a gap-analysis generated by CIAT, partners of the project are collecting crop wild relatives of 29 of most globally important food crops and making them available to breeders so that more resilient varieties will be created.

The project is in the thick of the collecting phase and before long we should have an impressive portfolio of crop wild relatives collected, protected and prepared for the development of new, better adapted, crop varieties. Proper handling of the seeds is important for maximising their longevity in storage. When subjected to certain conditions, seeds can remain in storage for tens and sometimes hundreds of years and still be able to germinate into a living plant. Luckily this means that the seeds can come to our aid against the unforeseen challenges of future.

There are two crucial components to successful seed storage: drying and freezing. If you want to store seeds and delay their germination, you need to keep them dry. Freezing them increases their longevity even further by slowing down metabolic reactions in the cells of the seed.

Seed storage and agriculture

Humans use this adaptation of seed dormancy to their advantage. Since the dawn of agriculture farmers have been safeguarding seeds to ensure the harvest for the following year. Conservation of plant genetic resources, including crop wild relatives, also allows breeders to develop new crop varieties that are tastier or more resistant to disease.

Seed drying

Once seeds have been collected keeping them dry is the number one priority for every seed collector. There are a few tricks of the trade that every good seed collector keeps with them.

1. Bag it up

Seed collectors think carefully about the kind of bag they choose to keep their collections in. Cloth, paper or plastic bags it depends on what seeds you are collecting. (Read more here)

2. Keep an eye on the weather

Besides checking to see whether you need sunscreen or your waterproofs, looking up the climate of the region, and even the weather forecast for the day is an essential part of the planning for a successful seed collecting trip. E.g. Some seeds are particularly susceptible to deterioration from moist air conditions, such as those collected during the rainy season. These wet seeds need to be dried as soon as possible and this can be done by:

- spreading them out in a thin layer on some newspaper in the shade

- raising them off the ground to allow air to circulate beneath

- repacking them before nightfall to minimise moisture absorption as the

ambient humidity rises

Every seed counts so we cannot afford to be cavalier with our post-harvest handling!

3. The big blue drum

One way that the Millennium Seed Bank helps partner countries to make high quality seed collections when there is no dry-room nearby is to send them a large, 60 litre, blue drum containing sachets filled with dried-out silica gel.

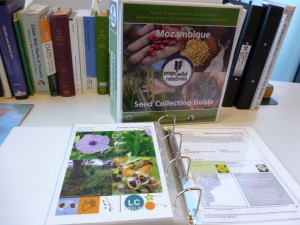

Shipped to partners of the Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change project, it is part of a ready-to-go tool kit for the perfect seed collecting expedition. Dissection kits, hand lenses, herbarium presses, collecting guides, GPS, and a first aid kit are among some of the goodies you will find inside. To find out more about how silica is used to dry seeds read here.

Back at the Seed Bank

Seeds can spend up to 6 months in the dry room, only taken out for the brief time it takes for them to be cleaned and counted. Only when the seeds have reached 15% relative humidity are they ready to go into cold storage in the -20°C seed vault.

A final word on rebel recalcitrant seeds

Some seeds, such as mango and Coco de Mer, cannot survive the drying and freezing process and are therefore difficult to store. These seeds are known as recalcitrant or unorthodox seeds and at the moment their only hope (for ex situ seed conservation) is cryopreservation in liquid nitrogen.

Related Links

The importance of seed drying for long-term seed storage