Category : News

Published : August 7, 2014 - 1:31 PM

In the following Q&A, Dr Eastwood, Crop Wild Relative (CWR) Project Coordinator from Kews Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) talks to us about the collecting, protecting and selecting CWR with the aim of ensuring our major crops can be adapted to grow in our changing climates.

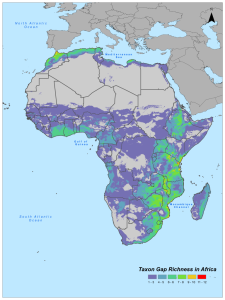

The Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change project is a ten-year project divided into three phases. In Phase I a Gap Analysis was carried out to indicate where CWR still needed to be collected. In Phase II, the current phase, project leaders Crop Trust and MSB work with partners from around the globe to secure high-quality seed collections. Phase III will see the use of CWR material.

1. Following the Gap Analysis results and the successful Training Course in Vietnam, the CWR Project is getting ready for a new capacity building effort this time in Africa. Please tell us more about this.

Our job now is to work with partners to secure high quality seed-collections across the globe.

We are holding a training course on collecting and conserving crop wild relatives (CWR) in Kampala, Uganda in collaboration with the National Agricultural Research Organisation. Interest in receiving training was very high and participants will be joining us from 8 African countries.

The week-long training course will take place during the week beginning 11th August and kicks off the African regional work in the project.

It is important that the skills of seed collecting and storage can be shared. The use of material to plant breeders and farmers depends on the quality of collection and storage. For Kew and the Crop Trust it is wonderful to be strengthening ties with the participant institutions.

2. Tell us about the actual day-to-day training course activities.

The course is a mix of fundamental theory and applied hands-on training. It is led by experienced experts from the MSB. Participants will learn how to plan collecting trips, assess populations for collection, collect field passport data, and use a drum drying kit and store collections safely, among many other things.

Participants will become familiar with the national Collecting Guides, which the project is providing to all national programs. These include identification tips, fruiting time data and suggested methods for collection.

Field activities will put the knowledge directly into practise. For example: participants will carry out cut tests on seeds to assess whether they are healthy.

3. Once the training week is over, what happens next?

We are already working with African partner organisations to plan how they will collect their national CWR.

The collecting ambition of each country program depends on the number of species in the country and how well they have been collected to date. In total the project aims to collect over 6,000 accessions.

When the participants attending the course return to their countries, they will be directly involved in implementing these national programs. It is envisaged that the first collecting expeditions will start in the autumn.

4. Once the collecting is done, what then?

The collected and cleaned material will be stored in the national genebank and a sample will be sent to the MSB for long-term safely duplication and for distribution to researchers and pre-breeders.

5. Looking at the bigger picture, please tell us why is it important to go after CWR?

Food security in the light of climate change is one of the greatest challenges the world faces.

We dont yet understand all the effects this will have so we need to have all options secured. One tool which has been show to contribute is improving crops using CWR.

CWRs have not gone through the domestication bottlenecks that have contributed to the limited genetic diversity within our crops. Whats more, they have continued to evolve in varied environments and climates. And it is known that they hold adaptive traits, some of which are unexpected and can only be discovered through breeding programs.

There is urgency to this work not only because the effects of climate change are already starting to be seen, but because the vital building blocks to allow us to adapt the CWR are threatened in their natural environments.

There is huge pressure on use of land for agriculture, housing and recreation, all of which impacts negatively on biodiversity.

6. Effects of climate change are predicted to be felt most strongly in sub-Saharan Africa.

Yes, and CWR of Aubergine, Finger Millet, Pearl Millet, Rice and Sorghum all of which are found in Africa could be used to adapt agriculture.

Food security is a global issue and no country is self-sufficient for its food. Thus the CWR project is not just working in Africa, it has a global outlook. CWR from other regions of the world could also help to improve African agriculture.

7. Can you tell us what other efforts that have been carried out by the CWR project?

Last December a similar training course was carried out for Asian partners in Viet Nam and from this project plans for collecting are well-developed.

Collecting has already started in Portugal, Cyprus and Italy.

The first 100 collections have already been received at the MSB and many more are expected in the autumn.

8. Any last words?

This project is unusual in its scope. It will not only secure CWR but will start to unlock their potential through pre-breeding programs.

CWR hold solutions for the future and through the support of the Norwegian government the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the Global Crop Diversity Trust are able to work with partners to leave a legacy of potential for the next generations.